Book Review: The Inventory of Henry VIII: Clothing and Textiles

The book itself costs an arm, leg and kidney. If I’d had to buy it for myself before Christmas, I’d have refrained. But now, having read through it, I have to say that it’s worth every penny I didn’t have to pay for it; and if I hadn’t got it for Christmas, I’d be saving up for a copy even now.

So, in the spirit of enablement, I’m passing on the details of just what’s in this book to all y’all, so you have an idea of whether or not you need to buy it. I initially intended to make it a facebook post to my historic costume list. two typed pages later, I had to reconsider; each one of the articles in the book deserves its own review.

The book is a series of essays, each one based upon the information on a particular topic to be found in the various inventories of Henry VIII, each written by a person at the top of their game in that particular field. The first is on King Henry’s Tapestry collection, written by Thomas Campbell. Then comes the section on the clothing of King Henry, and his hunting equipment, by Maria Hayward. She also writes the following section, on the textiles, tents, flags and costumes that were in the care of the Office of Tents and Revels.

This is followed by an article on table carpets and coverings for tables, seats and floors by the esteemed late Donald King, “The Art of the Broiderers” by Santina Levey, and a section on table and bed linens by David Mitchell. Then comes an article focusing on the textiles in Henry’s Store, by Lisa Monnas, another essay by her on the ecclesiastical textiles and costume in the inventory, and finally, an article on Furs in Henry’s wardrobe by Elspeth Veale.

A solid block of knowledge, indeed! 365 pages of brand new research on Tudor textiles and costume and I was determined to go through every page, even the sections I didn’t really expect to enjoy, like the articles on tapestries, carpets, table linens and ecclesiastical textiles. Even if they were dry, or ancillary to my interests, they were bound to be extremely informative and I was duty-bound to read them.

I had forgotten something, however. When a person is truly and whole-heartedly obsessed with a particular subject, and when they can write well, their love of it becomes infectious. They pass on the contagion of their passion via the written word, captivating the unsuspecting reader and carrying them along into unexpected areas of research.

Such was the case with these essays, even the ones on subjects that I hadn’t thought would captivate me at all. Like:

The Art and Splendour of Henry VIII’s Tapestry Collection

by David Campbell

Campbell answered questions about King Henry’s household textiles that I’d never thought to ask: what was his tapestry collection like? Why was tapestry so popular? How expensive was it relative to other decorations? What did particular tapestries mean to their viewers: their presence, the detail of their construction, and their content? Where did King Henry get his tapestries? What subjects did he prefer, and why? How did his tastes differ from his son/s How did the changing economic climate in Europe affect tapestry production? And the final question: Henry had over 2,400 tapestries when he died. Where on earth did they all go, and why are virtually none around today?

Campbell answered questions about King Henry’s household textiles that I’d never thought to ask: what was his tapestry collection like? Why was tapestry so popular? How expensive was it relative to other decorations? What did particular tapestries mean to their viewers: their presence, the detail of their construction, and their content? Where did King Henry get his tapestries? What subjects did he prefer, and why? How did his tastes differ from his son/s How did the changing economic climate in Europe affect tapestry production? And the final question: Henry had over 2,400 tapestries when he died. Where on earth did they all go, and why are virtually none around today?

These discussions are accompanied by page after page of brilliant, full color images of tapestries.

Dressed to Impress: Henry VIII’s wardrobe and his equipment for horse, hawk and hound;

by Maria Hayward

This section covered the clothing of King Henry and was, to my surprise, less absorbing than the section on Tapestries. Less because the subject material wasn’t interesting—it was, most definitely—but because I already knew the majority of what was discussed: King Henry’s clothing, how it was made, who made it, what it looked like, the materials used, etc. A substantial amount of the material reflected the content of Hayward’s comprehensive book Dress in the Court of Henry VIII, though with added detail focusing on the inventory contents themselves.

His coronation and garter robes are discussed, as are his hats, shoes, walking staves, and equipment for horse, hound and hawk. A section on the clothing of Arthur, Jane Seymour and Catherine Parr was particularly interesting.

The things that I enjoyed most in this article were some of the tables of distilled and concentrated wardrobe information: Lists of the Perquisites given to the officers of the wardrobe of robes, for one. This was an excellent window into what the servants of the King wore, or at least, the clothing they received, between 1516-20.

A few pages after this comes a table summarizing the different types of garments, alterations, and accessories found in King Henry’s wardrobe across the span of three inventories taken. Additional tables lay out what materials were used to make how many of each type of garment, and what colors were found in which types of garments.

A final table categorized the decorative and construction techniques used on particular types of garments; for example, of King Henry’s hose, one was bordered, nine were cut, three were edged, 15 were embroidered, one was fringed; 13 were decorated with Venice gold, and four with Venice silver.

My favorite part of this article was…yes, I admit it…the endnotes. When it comes to historic costume, I am an endote junkie. You never know what you’re going to find there: references to previously unknown manuscripts, unknown books, even references to books in your own collection that you had no idea contained the information referenced. And Hayward can always be depended upon to reference all sorts of mouthwatering manuscripts and accounts. She has them in spades. I collect the most tantalizing ones, saving them up for my next trip across the pond, so I can order them up at the British Library or Public Records office and roll around naked on them transcribe them for my own nefarious purposes.

In fact, one of the footnotes in this book started me on an entertaining ramble through my own collection. A reference to a farthingale owned by Princess Elizabeth in 1545, made of Satin of Bruges, sent me down to the footnotes to find out more about it. The footnote took me to Dress in the Court of Henry VIII. When I found the quote there, it too was footnoted…back to Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlock’d. And when I opened up QEWU to the cited page? You guessed it—it was footnoted too, referencing Costume in the Drama of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries.

By now, a bit exasperated, I opened up CoDS, fearing that I was about to find Planché or Norris. But! Finally, I found a reference to the actual wardrobe account mentioning the entry.

A wardrobe account with a catalog entry that looked naggingly familiar. I fired up my computer and poked around the manuscript warrants I’d photographed 10 years ago at the Public Records Office in England. Sure enough, there it was: one of the many I hadn’t gotten around to transcribing yet. Talk about coming full circle!

Temporary Magnificence: the offices of the tents and revels in the 1547 inventory;

by Maria Hayward

This section was another happy surprise. My exposure to Tudor tents and revels has been heavily revels-centric, to date. I’d read many works on revels, the costume and sets and social meaning assigned to them, the evolution into the Jacobean masque, etc., etc. I had Feuillerat’s transcription of the wardrobe warrants for the revels, and had focused upon the costume-related aspects of them. But tents? Not so much.

This article remedied that lack. Tudor tents: what they were made of, how they were decorated, what they looked like, practical construction details like windows made of translucent Holland cloth, wooden buttons for hanging the walls, Crow foot ropes, eyelet holes reinforced with calfskin leather, and more. Dimensions for the individual pieces of roofs and tent sides are given, as were descriptions of the various types of tents needed for campaign–including kitchen tents–and what was needed to furnish them.

My imagination was further fired by the glorious pictures of tents and encampments, and by the vivid descriptions of the king’s tents. One, a huge sixteen-sided tent, had a map of the world painted on the interior of the roof and had a center support made of a ship’s mast.

Another description of a “royal tent” resembled a minor village: One 10 x 15 foot “porch”, a pavilon 18 feet wide, and a 10 x 30 foot hallway leading from this to the first great chamber (16 x 40 feet). This chamber was connected to the first hall (10 x 34 feet), and a 15 x 50 foot “great chamber”. Additional 10 x 30 foot hallways led across into two more pavilions and a timber-framed “house” covered with gloriously painted canvas.

Talk about camping in style! The description of his timber house made me want to rush out and build one myself for next Pennsic: “…a timber house all of Firre painted and gilted with a square tower at every ende and corner, all covered with white plate scallape wise and sealed within with paste work painted, the windows of horne with all beastes vanes and vices belonging to it. ”

This section was followed by an excellent overview of Tudor revels and disguisings. It wasn’t terribly in-depth, but covered the important aspects of revels, what was worn, their place in the social fabric of the court, and the structure and function of the office of revels. It is accompanied by lovely descriptions of a variety of the costumes themselves, bringing the revels to life.

From the Exotic to the Mundane: carpets and coverings for tables, cupboards, window seats and floors

Donald King

The section on carpets was the shortest in the book: 12 pages. It did a good job of discussing what kinds of carpets were used in Tudor houses, and how they were used, and where they came from.

The Broderers’ Work;

Santina Levey

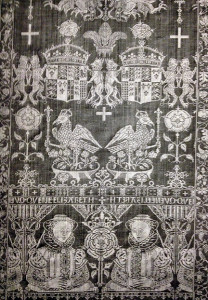

Ah! Tudor embroidery! This section impressed me, not only with its illuminating and clear descriptions and definitions of all of the varieties of embroidery and embellishment used at the Tudor court (each variety accompanied by inspirational photographs of items thus decorated), but by the information on how it was used: embroidery for beds, heraldry, cloths of estate, cushions, carpets, books and more are discussed, all with quotes and references to original items to lend color and life to the information.

Levey has a good section on quilts and quilted decoration, for those people interested in that particular topic. Among other useful factoids I learned that Tudor cutwork was not at all the same thing as the later Elizabethan cutwork: the former was a type of appliqué of fabric upon fabric, rather than the decoratively stitched and snipped linen that “cutwork” came to mean during Elizabeth’s reign. Cutwork was apparently a preferred method for embellishing revels costumes, as it looked impressive and could be accomplished much more swiftly than other forms of decoration.

Levey also takes the time to discuss the embroiderers themselves: the guild structure, female embroiders and their role in the industry, and a captivating portrait of William Ibgrave, broiderer to the king. She discusses the sorts of embroidery that was performed by them—embroidery of garter robes, livery, etc—as well as the sorts of needlework performed by the various women at Henry VIII’s court.

All in all, this was one of my favorite sections. It had richness, depth, was written in a very interesting and engaging manner, and was spectacularly illustrated with color photographs of various types of embroidery. A chapter guaranteed to make you want to rush off and try your own hand at couching gold bullion.

‘One Coverpane of Fine Diaper of the Saluatcion of our Ladie’: napery for tables and linens for beds;

David Mitchell

I admit it: this was one of the sections that I had girded my mental loins to plough through, regardless. I mean, let’s face it—after pages and pages of silk, velvet, gold and brocade, tablecloths are a bit mundane.

I admit it: this was one of the sections that I had girded my mental loins to plough through, regardless. I mean, let’s face it—after pages and pages of silk, velvet, gold and brocade, tablecloths are a bit mundane.

Once again I was pleasantly surprised. Linen, as it turns out, contains as much variety within the one fiber as any Great Wardrobe store. David Mitchell describes the different kinds of linen used: plain, diaper of damask work, diaper of birds eye, or diaper of crosse diamonds—and follows this up with a lovely technical discussion on the technology of linen damask and diaper weaving.

If you are interested in exactly how the King ate with linen—sizes of the napkins used by servants and how they were placed, widths of tablecloths, etc–Mitchell has that too. He has many close-up photographs of a variety of extant linen damask fabrics, and a table listing different damask patterns used in the Tudor court.

His description of all of the layers of a Tudor bed caught my fancy. There were many: bedstead first, then canvas, then a feather bed and a bolster/pillow, and then a layer of fustian—presumably to help soften the prick of straw and feather quills that worked their way through the feather bed—and then, finally, the bottom sheet. The fustian and bottom sheet were tucked under the featherbed all round, and the top sheet came after that. Some of the sheets were very ostentatious, bearing gold fringe, tassels and buttons.

After the top sheet came another fustian, and then, finally, the counterpanes, quilts, coverlets and other coverings. Two pillows of down with fustian ticks were typically provided.

The article is followed by a listing of all the inventories used in the article, with their full name, status, document reference number, date and location where they’re held: 50 inventories in all. Bless you, David Mitchell!

‘Plentie and Abundaunce’: Henry VIII’s valuable stores of textiles

Lisa Monnas

This next section, like the one before it, was more than I expected. After all that had come before, what more was there to say about the king’s store of textiles? I think of textile stores and envision the pages upon pages of monotonous listings of velvet, satin, silk and sarcenet I’d seen in the wardrobe accounts and inventories. Hardly a inspirational source of raw material.

This next section, like the one before it, was more than I expected. After all that had come before, what more was there to say about the king’s store of textiles? I think of textile stores and envision the pages upon pages of monotonous listings of velvet, satin, silk and sarcenet I’d seen in the wardrobe accounts and inventories. Hardly a inspirational source of raw material.

But it reveals a lot, as it turns out, and all of it fascinating. Lisa Monnas really hit it out of the park with this essay.

This section contains such gems as a table of “Prices paid for the textiles listed in the great wardrobe”, grouped by textile type and color. Another table lists how much of what type of red fabric was given to every member of the royal household for Edward’s coronation, clearly illuminating the vast ranks of people needed to run the machinery of the Tudor court, as well as their relative rank. It amused me that the yeomen of the Jewel house, Laundry, Ewery, Chandry, Spicery, Waffery, Buttery, Cellar, Poultry (Yes, there is a yeoman of the poultry), yeomen ushers, yeomen porters, and all of the other several dozen flavers of yeomen were given red cloth…but the yeomen of the wardrobe somehow ended up wearing crimson damask and crimson velvet.

There is good detail on just what fabrics were given for livery, and how much; what fabrics were worn by the King over the course of his reign, and how those fabrics changed; and a brief exploration of the mysterious lack of Venetian silks.

We also get a look at the caretakers of the fabric and the suppliers that provided it. Lady Somerset was spotted skulking out of the wardrobe store after Henry’s death with a fortune in fabric wrapped up in a sheet. Mercers and other purveyors of rich fabrics regularly went on progress with King Henry, having the latest velvets and cloths of gold sent to them on the way so that they could continually present the king with something novel. The 33,000 yards of black fabric required for King Henry’s death were provided by over 72 london cloth sellers. I can just imagine the frantic searches performed by the king’s household, looking for every scrap of black fabric they could find…and the cursing and grumbling of the London tailors attempting to fulfill their commissions, when black cloth couldn’t be had for love or money.

The exhaustive documentation of the wardrobe is also entertaining. Each package of silk had a label stating its contents, whether it was old or new, and from whom it was obtained, and when, as well as the price of the silk. Clerks kept track of every delivery: to whom it was made, what use it would be put to, and what piece was used. The “charmed inner circle” of courtiers that received these textiles is described by Monnas.

And all of this isn’t even the heart of the chapter: a complete descriptive listing and definition of all of the fabrics found in the wardrobe. Taffeta, Sarcenet, Satin, Velvet, etc. What it looked like, how it was woven, the different varieties found, what they were used for, where they were obtained from, and technical details (and diagrams) showing the weaves of the fabrics.

Her section on cloth of gold shows an impressively technical knowledge of the subject, and her section on cloth of tissue is positively outstanding—for the first time I have a firm and solid grasp on exactly what each of the various varieties of cloth of tissue looked like and how they were made.

Plus, a full compliment of color photographs of extant fabrics and of portraits showing the same, and nine full pages of excellent end notes. Yes, I can definitely say that this section really was my favorite of all of the essays in the book.

The Splendour of Royal Worship

This article covered the ecclesiastical textiles in the inventory: textiles for the chapel and vestments for the ecclesiastical functionaries that tended them. I really wish I’d had this article back when I was researching the cutting and cleaning of ecclesiastical clothing in the Nurnberger Kunstbuch manuscript; it describes who wore what kind of garments, where, and when. Copes and dalmatics and albs, oh my. What colors were worn; how the garments moved from place to place over time; what happened to them over the years; a very thorough look at ecclesiastical garments in general.

From Sable to Mink

This last section was one of the shorter ones in the book. It gave an overview of the various furs used in the wardrobe of the king and his court; the animals they came from and how they were used. The information was solid, and definitely useful to someone wanting to know more about furs in Tudor dress; but it was fairly superficial when placed next to the depth of knowledge displayed in some of the other sections. I’d have been interested in the technical details of how the furs were prepared and sewn; a bit more about the economics of the fur trade; perhaps even biographical details on the furriers and artisans involved with the gowns, if such existed.

The fur pampilion has been a mystery to me for some time. The Dictionary of Fashion states that it was a form of fine budge from Pamplona, and also a felt, but with no citation; Hollyband, in 1598, describes it as a coarse rug; and in 1598, the Duke of Richmond’s inventory mentions “another [whole fur] of pampilion and budge.”

So when I caught a mention to pampilion in the article I was eager for more information…but none was forthcoming. Not even a footnote, alas.

Another fur that had stumped me in Elizabth’s wardrobe accounts, lybard wombs, was also mentioned in the article. Was it leopard? Something else? But again, no description of what it was.

And lastly, we have the bibliography. You know a bibliography’s going to be good when the first page consists entirely of unpublished primary sources–so considerate of them to group them together like that. Then comes “Published Primary Sources”, “Unpublished papers and dissertations”, and only then the eight pages of secondary sources. I think I spent more time on the bibliography, noting down sources to follow up on, than I did on any single article in the collection.

Conclusion

Usually, in cases where a book is published as a series of articles on a topic written by different authors, there’s a lot of dross to wade through the come to the gems that cover your particular area of interest. This book is an exception to that rule. It is chock full not only of superior information on all aspects of Tudor dress and costume, but also several jumping off points into other sources to help further your research. It’s rare that a dense reference book is such a good read.

Leave a Reply to Drea Leed Cancel reply