By Danielle Nunn-Weinberg

|

"Waters she hath to make her face to shine, Confections, eke, to clarify her skin; Lip-salve and cloths of a rich scarlet dye She hath, which to her cheeks she doth aply; Ointment, wherewith she sprinkles o'er her face, And lustrifies her beauty's dying grace." |

C

osmetics have been used since ancient times. However, they fell into disuse in most of Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. It was not until the return of the men from the crusades that Europe saw the return of beauty and hygiene aids it had long forgotten.

C

osmetics have been used since ancient times. However, they fell into disuse in most of Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. It was not until the return of the men from the crusades that Europe saw the return of beauty and hygiene aids it had long forgotten.

The concept of cosmetics as "face paint" did not really begin to resurface in Northern Europe until the 14th century. Even then, cosmetics were not commonly used outside of the bawdy trades. The one exception to that rule seems to be "blanchete" or wheat flour. Women whose complexions were "ruined" by the sun used blanchete on their faces to regain the roses and lily complexions, which were so prized by the chivalric ideal. This ideal coloured the perception of beauty until the end of the SCA period.

The epitome of the fair skin and fair hair ideal seen throughout the later Middle Ages and Renaissance is presented in Botticelli's Birth of Venus. Venus, as the goddess of love and beauty, represents the icon of beauty that women would have aspired to. In order to attempt to achieve this, cosmetic lotions and powders of various sorts were employed. It is during the Renaissance that the use of cosmetics crossed trade and station boundaries to become popular with almost everyone. This article will discuss some of the cosmetics found during the later Middle Ages and Renaissance by looking at extant recipes, and suggest ways in which they might be adapted for use by recreators. Terms for ingredients which might be unfamiliar are covered in a glossary at the end of this article.

One excellent source of information for beauty instruction in the 16th century is a conversation manual commonly referred to as "A dialogue of the faire perfectioning of ladies." It is written as a discussion between two kinswomen, Raffaella and Margaret. The elder, Raffaella, is guiding her younger kinswoman Margaret through the intricacies of social life.

| Raffaella: "Thou must know, Margaret, that a young lady could not have a complexion so clear, white and delicate if she did not aid it to some degree with art, or else it might show at times by mischance as might often happen, that it is not so fair. And they do not reason well who say that a lady, so she have a fair complexion by nature, may ever thereafter set it at naught and neglect it. And for this cause I would grant that a gentlewoman should use continually waters of price and excellence, but without solid matter to them or but the very least part. And for these I may know to give you receits most perfect and most rare."2 |

There are numerous extant cosmetic recipes in many different sources. However, there are a couple of major problems that a reenactor would have with these recipes: the toxicity of some ingredients, such as mercury and lead, and the scarcity of other ingredients such as ambergris, which comes from sperm whales, civet, which comes from polecats, and musk, which comes from the male musk deer.

Given the number of comments in period sources that remark to the effect that "this recipe will no damage your skin and teeth like those other ones", it can be extrapolated that people, toward the end of the SCA period, were becoming aware of the harmfulness of many of the cosmetics used.

The downside to the use of face whitening substances is described well by the two kinswomen, Margaret and Rafaella.

|

Margaret: "Then these sublimates and white powders and many other sorts of soap-lyes seem not to you to be commendable."

Raffaella: "Nay rather, they are the most blame-worthy. For what worse can we see than a young lady who has powdered herself with chalk, and has covered her face with a mask so thick that scarce may it be known who she is."3 |

This argument was further illustrated by Margaret's description of a lady of their house.

| "...so unhandsomely had she covered her face that I promise you her eyes seemed those of another woman; for the cold had made her complexion of a ghastly colour like lead and dried plastering so that the poor woman had to stand stiffly and not turn her head but with her whole body for fear the mask should split."4 |

Although many of the recipes for lotions and face-whitening substances contain harmful ingredients, the following lotion, which was considered to be common, seems to be less dangerous than most, although I do not imagine that alum and verdigris are precisely good for you. It is also worth noting that apparently, the use of these cosmetics were not confined to women:

| Raffaela: "I know what lotion that is and it is sold to many; for now almost all ladies use it, since it costs but, little (and not ladies only, but many more of those womanish young fellows who had done better to be born women than men). The lotion is made up of Malmsey wine, white vinegar, honey, lily flowers, fresh beans, verdigreese, right silver, rock salt, sandiver, rock alum and sugar alum; every element distilled in a limbeck. And it is in truth a very good lotion, but for divine waters I would give place to no-one in this world, and especially for one of them, very costly indeed but, of very great excellence."5 |

The toxicity of most of the whitening lotions is clearly evident in this recipe from Raffaella, which is apparently meant for a common person.

| "...One takes pure silver and quicksilver and, when they are ground in the mortar, one adds ceruse and burnt rock alum, and then for a day they are ground together again and afterwards moistened with mastic until all is liquid; then all is boiled in rain water and, the boiling done, one casts some sublimate upon the mortar; this is done three times and the water cast on the fourth time is kept together with the body of the lye. And this is used oftentimes among ladies who have no great means to spend."6 |

I find it interesting that the following recipe, which was meant for wealthier people, might actually be a little bit better for the skin because of the inclusion of the almond oil. Mercury was known to be a drying agent and was used by physicians to dry out weeping sores. I would also be curious to know whether or not the addition of the silver and pearls would change how the final product looked.

| Raffaella: "...One takes the finest true silver and quicksilver [mercury] passed through buffin cloth, and when blended together they are ground for a day in the same direction with a little fine sugar. Then I take it from the mortar and grind it on a painter's porphryry slab, and I embody therein shreds of silver and pearls. Then anew I grind all the things together upon the porphryry and set them back in the mortar and next morning early I slake them with foam of mastic with a little oil of sweet almonds; so when the liquid has stood for a day I slake all again with water of dittany and put it in a flask and bring it to the boil in a Mary's Bathe lymbeck. Then having done this four times, ever casting out the water, the fifth time I conserve it and drawing it from the flask I void it into a bowl and let it settle. Then anon I empty out the water softly, and at the bottom the sublimate remains with which I mingle woman's milk and give it savour with musk and ambergrease. Al this I mix together with the water and store it in a well-stopped flask in my cellar below ground."7 |

As you can see, most modern people, no matter how ardent they are about authenticity, would probably not actually use these concoctions on their skin. There was one recipe I did find which might not be too bad to use, if somewhat hard to come by. However, I would probably substitute almond or another safe and readily available oil for the white poppy oil mentioned in the recipe. For reenactment purposes one could probably also substitute white theatrical powder for the ground bone.

|

A white fucus or beauty for the face. "The jawe bones of a Hogge or Sow well burnt, beaten and searced through a fine searce, and after ground upon a porphire or serpentine stone is an excellent fucus, being laid on with the oyle of white poppey."8 |

It should be noted that the neck and exposed breasts were also painted white. Sometimes blue veins were drawn over the whitened breasts.

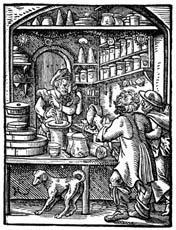

While that covers the lily half of the complexion, the roses aspect was given equal attention. I find it interesting to note that amongst all the recipes for other lotions and paints there do not seem to be any for the red used on lips and cheeks. To me this would suggest that it was not something that was usually prepared at home but bought from a peddlar or an apothecary. The most common red colour used seems to have been vermillion, which was an orange red.

While that covers the lily half of the complexion, the roses aspect was given equal attention. I find it interesting to note that amongst all the recipes for other lotions and paints there do not seem to be any for the red used on lips and cheeks. To me this would suggest that it was not something that was usually prepared at home but bought from a peddlar or an apothecary. The most common red colour used seems to have been vermillion, which was an orange red.

Vermillion is red crystalline mercuric sulphide. The pigment was applied by mixing it with gum arabic, egg whites, and the milk of green figs. Other reds that were used were derived from red ocher, madder, cochineal, brasil wood that had been steeped in water and applied with fish glue, and red sandalwood. Margaret, in the "Fair perfectioning of ladies," mentions that in some cases the red used for the cheeks was put on before the white in an attempt to make it look more natural by supposedly making the complexion "incarnate" or flesh-coloured.

White teeth were considered as important as a white face in the 16th century beauty ideal. Therefore, dental hygiene was encouraged, but compared to modern standards, it was somewhat lacking. Here is one recipe for powder to clean the teeth, which guarantees the whitening of teeth and fresh breath after only a few days of use (though I imagine that with long-term use, this abrasive powder would remove the teeth issue altogether.)

| "Take three drachms each of crystal, flint, white marble, glass and calcined rock salt, two drachms each of calcined cuttlefish bone and small sea-snail shells, half a portion each of pearls and fragments of gemstones, two drachms of the small white stones which are to be found in running water, a scruple of amber and twenty-two grains of musk. Mix them well together and grind them into the finest powder on a marble slab. Rub the teeth with it frequently and, if the gums have receded, paint a little rose honey on them. The flesh will grow back in a few days and the teeth will be perfectly white."9 |

Another recipe I found is a good deal less labour-intensive, but I doubt it was quite as effective for whitening the teeth:

| "To keepe the teeth both white and sound. Take a quart of hony, as much Vinegar, and halfe so much white wine, boyle them together and wash your teeth therwith now and then."10 |

An interesting fashion originally related to the teeth was the beauty patch. A black velvet or taffeta "mastic" patch was originally worn on the temple to relieve toothaches. However, towards the end of the 16th century this became a beauty item, worn to contrast the whiteness of the complexion.

One feature that was important to the beauty ideal in Elizabethan England was large, luminous eyes. It has been suggested that kohl, which was commonly used in the Middle East and Asia, was employed to emphasize the eyes. It has also been suggested that during the later 16th century, belladonna, or deadly nightshade, began to be used to enlarge the pupil and make the eyes more luminous.

One feature that was important to the beauty ideal in Elizabethan England was large, luminous eyes. It has been suggested that kohl, which was commonly used in the Middle East and Asia, was employed to emphasize the eyes. It has also been suggested that during the later 16th century, belladonna, or deadly nightshade, began to be used to enlarge the pupil and make the eyes more luminous.

Illusions of youth were as important to the image of beauty in the past, as these illusions are now. If you think about it, how many portraits of wealthy and powerful people show them grey-haired? Almost none. So, either all the artists were being generous and looking for the approval of their patrons by idealizing what they painted, or people had some way to deal with greying hair. Although wigs and false hair were commonly used, it appears that hair dye was as well. We have surviving recipes to turn hair gold, chestnut, or black.

I'm sure you aren't surprised that some of the recipes are harmful. This recipe for turning black hair to chestnut even comes with its own warning:

|

"To colour a blacke haire presently into a Chestnut colour. This is done with oyle of Vitrioll: but, you must doe it verie carefully not touching the skin."11 |

Surprisingly, the following method for achieving blond hair sounds like it might work; however, I wouldn't try it, given the lye.

| "Take a pound of finely pulverized beech-wood shavings, half a pound of box-wood shavings, four ounces of fresh liquorice, a similar amount of very yellow, dried lime peel, four ounces each of swallow wort and yellow poppy seeds, two ounces of the leaves and flowers of glaucus, a herb which grows in Syria and is akin to a poppy, half an ounce of saffron and half a pound of paste made from finely ground wheat flour. Put everything into a lye made with sieved wood ashes, bring it partly to the boil and then strain the whole mixture. Now take a large earthenware pot and bore ten or twelve holes in the bottom. Next take equal parts of vine ash and sieved wood ash, shake them into a large wooden vessel or mortar, whichever you think better, moisten them with the said lye, thoroughly pulverize the mixture, taking almost a whole day to do this but make sure that it becomes a bit stiff. Next pound rye and wheat straw in with it until the straw has absorbed the greater part of the lye. Shake these pounded ashes into the said earthenware pot and push an ear of rye into each small hole. Put the straw and ashes in the bottom so that the pot is filled, though still leaving sufficient space for the remainder of the lye to be poured over the mixture. Towards evening set up another earthenware pot and let the lye run into it through the holes with the ears of rye. When you want to use the lotion, take the liquid which ran out, smear your hair with it and let it dry. Within three or four days the hair will look as yellow as if it were golden ducats. However, before you use it wash your head with a good lye, because if it were greasy and dirty it would not take the colour so well. You should note that this preparation will last for a year or two and, if one goes about it properly it can help ten or twelve member of the fairer sex, for very few things will colour the hair."12 |

One item frequently listed with these recipes is the pomander or "scent apple," which was a solid perfume carried in a decorative holder. Although I would not necessarily call it a cosmetic, it is important in the overall beauty concept and usually grouped with the cosmetic recipes. There are a number of pomander recipes that have survived. The following recipe from 1573 struck me as one of the more pleasant ones:

One item frequently listed with these recipes is the pomander or "scent apple," which was a solid perfume carried in a decorative holder. Although I would not necessarily call it a cosmetic, it is important in the overall beauty concept and usually grouped with the cosmetic recipes. There are a number of pomander recipes that have survived. The following recipe from 1573 struck me as one of the more pleasant ones:

|

"To Make a pomander Take Benjamin one ounce, of storar calamite half an ounce, of laudanum the eigth[h] part of an ounce. Beat them to powder and then put them into a brazen [brass] ladle with a little damask [water] or rose water. Set them over the fire of coals till they be dissolved and be soft like wax. Then take them out and chafe them between your hands as ye do wax. Then have these powders ready finely searched [sifted]: of cinnamon, of cloves, of sweet sanders [sandalwood], gray or white, of each of these three powders half a quarter of an ounce. Mix these powders with the other and chafe them well together. If they be too dry, moisten them with some of the rose water left in the ladle, or other. If they wax cold, warm them upon a knife's point over a chafing dish of coals. Then take of ambergris, of musk, and civet, of each three grains. Dissolve the ambergris in a silver spoon over hot coals. When it is cold make it small, put to it your musk and civet. Then take your pome that you have chased and gathered together, and by little and little (with some sweet water if need be) gather up the amber, musk, and civet, and mix them up with your ball, till the be perfectly incorporated. Then make one ball or two of the lump, as ye think good, for the weight of the whole is about two ounces. Make a hole in your ball and so hang it by a lace."13 |

Another pomander recipe from 1609 is:

|

"A sweet and delicate Pomander. Take two ounces of Labdanum, of Benjamin and Storax one ounce, muske sixe graines, civet sixe graines, Amber greece sixe graines, of Calamus Aromaticus and Lignum Aloes, of each the waight of a groat, beat all these in a hote mortar, and with an hote pestell till they come to paste, then wet your hand with rose water, and roll up the paste sodainly."14 |

Adapted Pomander Recipe

Adapted Pomander Recipe

Ingredients

1/2 lb. Beeswax

1 tbsp. Almond oil

1 tsp. Ground cinnamon

1 tsp. Ground cloves

1 tsp. Powdered sandalwood

1/4 tsp. Amber paste

15 drops of Benzoin essential oil

Tools

Melt the beeswax over medium heat while stirring constantly. Once it is completely liquid, lower the heat and continue stirring. Do not let the wax or mixture boil. Stir in the cinnamon, cloves, and sandalwood. Stir until thoroughly mixed. Then add the amber paste and the benzoin. Once these are thoroughly mixed add the almond oil and mix completely. Once this is mixed together pour it into the foil-lined bowl to cool. Once the mixture is cool enough to handle roll into balls. This makes over a dozen one inch "pommes."

The pursuit of beauty during the later Middle Ages and the Renaissance was not an easy thing, despite the availability of recipes to suit all budgets. The long, time-consuming recipes and dangerous substances didn't seem to stop any woman (or man) who aspired to fashionable beauty. In this I find a certain amount of irony since we have continued this mind-set to the current times.

Ames-Lewis, Francis and Rogers, Mary, eds. Concepts of Beauty in Renaissance Art. London, 1998.

Angeloglou, Maggie. A History of Make-up. London, 1970.

Boeser, Knut, ed. The Elixirs of Nostradamus: Nostradamus' original recipes for elixirs, scented water, beauty potions and sweetmeats [1552]. London, 1994.

Camden, Carroll. The Elizabethan Woman. New York, 1975.

The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, 1981.

Corson, Richard. Fashions in Makeup: From Ancient to Modern Times. New York, 1972.

Furnivall, Frederick, ed. Caxton's Book of Curtesye. (printed at Westminster about 1477-8). London, 1868.

McLaughlin, Terence. The Gilded Lily. London, 1972.

Orlin, Lena Cowen, Elizabethan Households, An Anthology. Washington DC, 1995.

Plat, Sir Hugh. Delightes for Ladies, to adorne their Persons, Tables, Closets, and Distillatories: with beauties, bouquets, perfumes & waters (1609). Introduction by G. E. Fussell, and Kathleen Rosemary Fussell. London, 1948.

Raffaella of Master Alexander Piccolomini, or rather A dialogue of the faire perfectioning of ladies: a work very necessarie and profitable for all gentlewomen or other. J.N [i.e. John Nevinson] trans. Glasgow, 1968.

Romm, Sharon. The Changing Face of Beauty. St. Louis,1992.

Stubbes, Phillip. Anatomy of the Abuses in England in Shakspere's Youth [1583]. Frederick J. Furnivall, ed. London, 1877-9.

Williams, Neville. Powder and Paint: A History of the Englishwoman's Toilet, Elizabeth I Elizabeth II. London, [1957].

| © 2001 Danielle Nunn-Weinberg |