The Spanish Farthingale

Where did it come from? | The Spanish Farthingale in England | What was it made of? | How was it made? | Get a Farthingale of your Own

In Tudor and Elizabethan times,

The Spanish Farthingale was a bell-shaped hoopskirt worn under the skirts of well-to-do women. It played an important part in shaping the fashionable sillhouete in England, from the 1530s until the 1580s.

Origins

The Spanish Farthingale, as its name suggests, originated in Spain. The name "farthingale" itself is an English corruption of the Spanish "verdugado", a word for the Spanish word for wood, which refers to the rings of wood or willow osiers forming the rigid rings attached to the skirt. Alternate Elizabethan spellings of "farthingale" --verdingal, verdugal, and fardingal, etc--reflect this relationship.

The first Spanish verdugados are mentioned in the 1470s. By the 1480s and 1490s, they were a fixture of noblewomens' dress. A verdugado could have a series of single hoops, a series of doubled hoops, or in some cases, even three hoops set together at the bottom of the skirt. In some cases, the rigid hoops were replaced by bands of fabric trim or cord, reflecting the look of the verdugado without the stiffness.

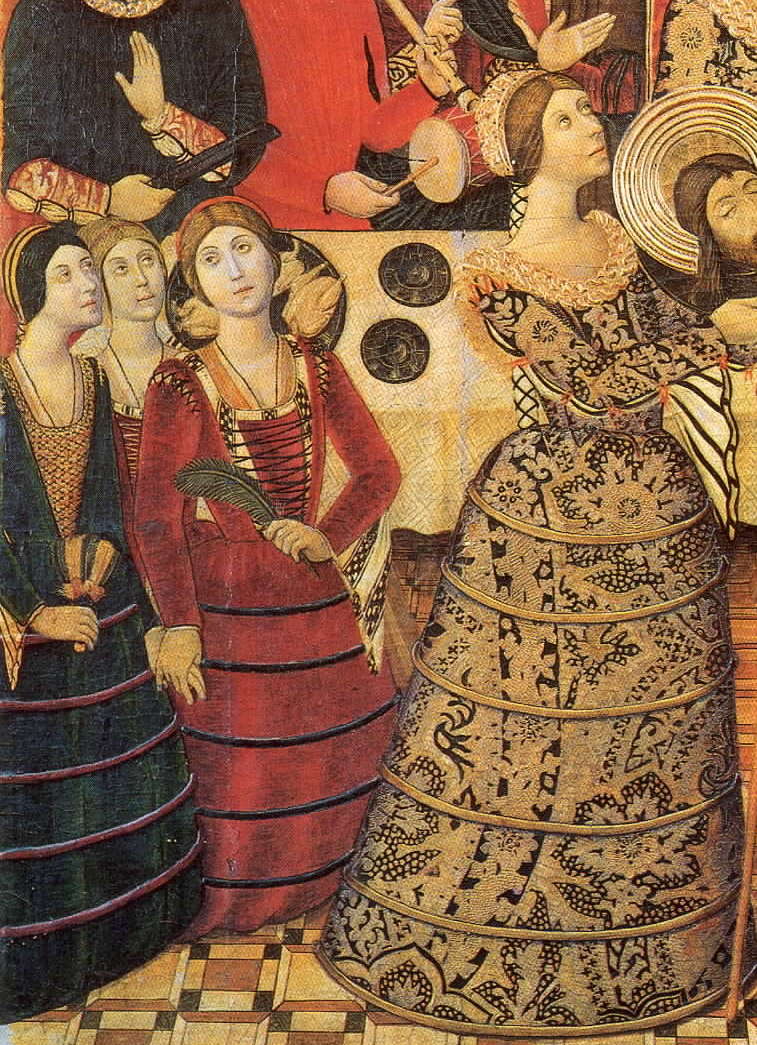

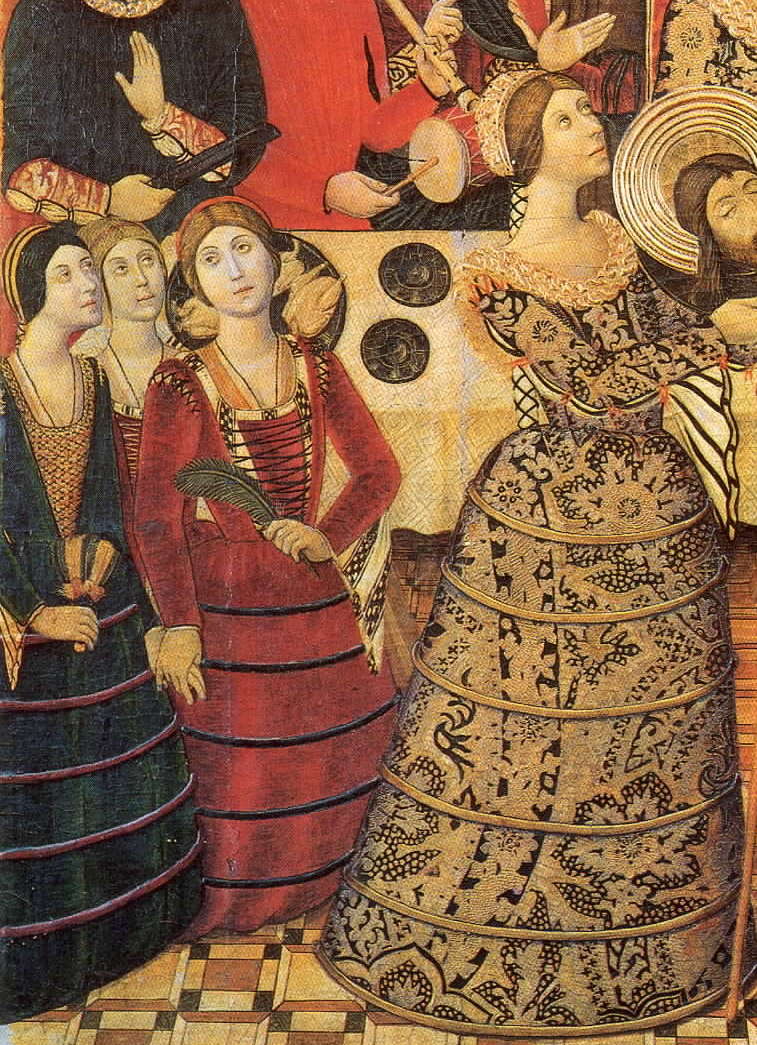

Hoops of cane covered with what appears to be velvet are applied directly to the outer skirts of the womens' gowns.

Detail from The feast of Herod, by Pedro Garcia de Benabarro, c. 1475.

Note the doubled bands on Salome's verdugado. The brocade pattern continues over both bands, suggesting that one strip of fabric was wrapped around two canes, and the hoop stitched to the skirt between the canes.

Detail from The Decapitation of John the Baptist, by the Maestro of Miraflores, c. 1490.

A skirt with stiffened bands of fabric applied in lieu of verdugos (willow canes).

El Cancionero by Pedro Marcuello,1495. Museo Condé Chantilly, France

Note the puckering on the leftmost woman's skirt, where the hoops have been attached. Also, the bottommost two hoops are doubled, for strength.

Detail of Spanish Women from The Trachtenbuch of Christoph Weiditz, 1505.

The Spanish Farthingale comes to England

Tradition holds that the Spanish Farthingale arrived in England in the early 1500s, introduced by Katharine of Aragon, Henry VIII's future queen. In a description of the marriage of Katherine and Prince Arthur in 1501, her clothing is described as:

"...her gown was very large, bothe the slevys and also the body with many plightes, much litche unto menys clothyng, and aftir the same fourme the remenant of the ladies of Hispanyne were arayed; and beneath her wastes certayn rownde hopys beryng owte ther gownes from the bodies aftir their countray maner."

Despite this early reference, it is only in the 1540s--four decades later--that clear evidence of a stiffened hoopskirt begins to appear in documents, portraits and paintings of the time. The classic mid-16th century English look is created in large part by the farthingale: an inverted small triangle of the bodice over a larger one of the skirt. Queen Mary Tudor had several farthingales in her wardrobe: two farthingales of crimson satin edged with crimson velvet, and one of crimson grosgrain edged with crimson velvet.

Catherine Parr by Master John, 1545

Elizabeth I by William Scrotts, 1546

Mary I by the English School after Hans Eworth, c. 1550s

Mary I by Hans Eworth, 1554

In the mid-sixteenth century, the Farthingale also enjoyed popularity in France. It appears in several portraits and books of fashion from the mid-sixteenth century.

Catherine de' Medici, Anonymous, c. 1550s

A Frenchwoman in the Frauen Trachtenbuch by Jost Amman, 1577

Detail from a plate showing the city of Orleans, France, from the book Civitates Orbis Terrarum c. 1588

The woman to the left wears a farthingale with doubled hoops; the woman to the right wears none. Detail from a plate showing the city of Orleans, France, from the book Civitates Orbis Terrarum c. 1588

The silhouette of the farthingale stayed for the most part the same through the 1560s and 1570s, widening slightly. It was worn under several styles of gown: the "French Gown", with its low square neckline and gathered skirt, as well as the English Gown and Strait-bodied gown, high-necked gowns with boned sleeves.

Margaret Audley wears a farthingale beneath her English Gown, with its boned upper sleeves and high-necked bodice with a turned back neckline.

Margaret Audley by Hans Eworth, 1562

Queen Elizabeth here wears a French Gown of crimson velvet with a farthingale beneath. The swelling at the hips was accomplished by padding the pleats with heavy frieze or wool batting, as well as by stitching a small padded roll around the inside of the pleats.

The Hampdon Portrait of Elizabeth I by Stephen van der Meulen, 1563

In this allegorical painting, Queen Elizabeth wears a farthingale beneath her kirtle and gown.

Elizabeth I and the Three Goddesses by Hans Eworth,1569

Queen Elizabeth out Huntting, detail from the Book of Hunting by George Turbervile.

Keep in mind, however, that the Spanish farthingale was worn by the wealthy. Commoners and even well-to-do merchants are frequently shown wearing gowns without farthingales. in The Fete at Bermondsey, one can see noblewomen to the left wearing farthingales, and commeners and merchants elsewhere who are definitely wearing none.

The Fete at Bermondsey by Joris Hoefnagel, 1569

The gentlewomen here are clearly wearing no farthingales beneath their gowns.

Gentlewomen of London and a Countrywoman by Lucas de Heere, 1570

The Spanish Farthingale continued to be worn in England through the 1580s, although its popularity waned as the French Farthingale gained in popularity. Even so, there are some images from the 1580s of Queen Elizabeth wearing a Spanish Farthingale, even after she had several French Farthingales in her wardrobe. Two of the portraits below show the difference in silhouette between the Spanish and French Farthingales: The first, by Gheerarts, shows the Queen wearing a gown with a Spanish Farthingale beneath it. To its right is the same image painted five years later, updated with a more fashionable French Farthingale'd silhouette and a wider ruff.

Here, Queen Elizabeth wears a rather unrealistic FOUS (Farthingale of Unusual Size). Elizabeth I Hilliard, 1585

The Welbeck Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I by Marchs Gheerarts, 1585

Portrait of Queen Elizabeth after Marcus Gheerarts, 1590.

What were farthingales made of?

Salome's farthingale was a decorative underskirt meant to be seen, and was therefore made out of an expensive brocade. In the 16th century, farthingales were mostly hidden under petticoats, kirtles and gowns--but for noblewomen, they were still made out of luxurious and brightly coloured fabrics.

In the inventories and wardrobe accounts of the time, the majority of the farthingales listed are made out of silk fabrics such as satin or silk taffeta, with the hoops covered with velvet, taffeta or satin. Frequently the color of the farthingale and the color of the fabric covering the hoops were the same (for example, Queen Elizabeth I had a white satin farthingale with the hoops covered in strips of white velvet), but the farthingales could be quite colorful. Elizabeth also had a green farthingale with pink bands over the hoops, a blue farthingale with yellow bands over the hoops, and even an orange and purple striped farthingale! This excerpt from Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Accounts, listing all the farthingales made and altered in the first half of 1579, gives some idea of the variety found in materials:

"

for .. enlarginge styffenynge and making lyter of a verthingale of carnacion satten the bent covrid with grene vellat layed with carnacion silke lase with bent : for styffenynge of a verthingale of oringe color taphata striped with purple & carnacion silke the bent covrid with like taphata: for enlarginge with a newe hind parte & styffenynge of a verthingale of carnacion satten layed on with brode lase and frenges of venice golde & silver with bent to it: for styffenynge & lyninge the foreparte of a verthingale of skeye color taphata the bent covrid with oringe color vellat: for styffenynge & lyninge the foreparte of a verthingale of white satten the bent covrid with white vellat: for thre sevrall tymes styffenynge of a verthingale of strawe color & watchett taphata the bent covrid with like taphata: for altering of a verthingale of carnacion satten and making it lesser: for translating of a verthingale of oringe tawnye taphata and making it longer: for styffenyng and enlarginge with a newe hinder parte of a verthingale of blak tufte taphata the bent covrid with like taphata: for making of a verthingale of strawe color buckeram the bent covrid with like colorid cloth

The woman here is wearing what appears to be a skirt stiffened with a continuous band of bent rope or other stiffening.

Detail from Il Libro del Sarto (The Tailor's Handbook), Anonymous, c. 1580

Other farthingales were made of coarser materials. The Ladies in Waiting of Mary Queen of Scots had farthingales made of buckram and fustian as well as cheap taffeta:

- Item iii elnis bukram to be hir ane wardegard, the elne iiis; (1552) Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, Vol X

- Item, ane wardegard of gray fustian to hir, liiiis (1552) Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, Vol X

- Item, vii elnis of tafeteis of the foure threidis to dowble ane werdingale (1562) Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, vol XI

If you wish to use the modern equivalents of these fabrics, be warned: bridal satin and acetate taffeta are both much weaker than silk satin or taffeta, and will not support the wear and tear and strain put upon a farthingale unless it is backed with a heavier fabric, such as cotton duck, drill, or canvas. If you do want to use silk satin or silk taffeta for a reproduction farthingale, Thai Silks has a wide variety of fabrics suited to this need. They are listed on the Costuming Supplies Page. A woman of lesser means would likely make her farthingale out of a heavy linen or linen-silk blend. Wool, as it stretches, is not a good fabric for a farthingale.

THe most common material for stiffening farthingales in the 16th century was "bent rope". This was a light, springy and flexible rope made out of the reeds known as bent grass. Queen Elizabeth used bent rope exclusively for her fartuingales until, in the 1580s, we begin to see references to whalebone used to stiffen her spanish farthingales.

Mary, Queen of Scots, used whalebone for at least some of the farthingales worn by her and her ladies in waiting:

- 12 bowtis of quhaill horne to be girdis to the werdingallis (1563) Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, vol XI

- Item, ane verdingale iiili xs; Item, v balling of quhail (1562) Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer, vol XI

Most recreation farthingales are made using hoopskirt boning. Hoopskirt boning is 1/2 inch wide stiffened canvas or plastic with spring steel along the edges. It is very stiff and can hold out the heaviest of skirts, yet is lighter than other boning materials. Because it is flat, rather than rounded, it doesn't create the bumps or ridges sometimes seen with farthingales made of period materials. Hoopskirt boning can be cheaply bought ($10.25 for 12 yds of boning) from mailorder costuming supply houses such as Greenberg & Hammer, which are listed on the Costuming Supplies Page.

Others choose to use lengths of rope, timber strapping, artificial whalebone, or other modern equivalents. For a more authentic reproduction, you can make your own "bent rope": take 20 pieces of 00 basket reed and bind them together into a long length with heavy thread, replacing individual reeds as you come to the end.

How were they made?

Although paintings showing the actual construction of a farthingale are rare, and no surviving farthingales remain for study, Juan de Alcega's Tailor's Pattern Book, published in 1589, provides invaluable information on the cut and construction of the Elizabethan Spanish Farthingale.

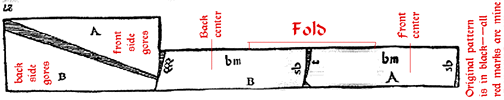

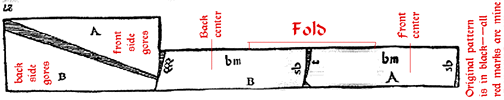

Following is his layout diagram, accompanied by his explanation of how to make a farthingale:

"To cut this farthingale in silk, fold the fabric in half lengthwise. From the left, the front (Piece A) and then the back (piece b) are cut from the double layer. The rest of the silk should be spread out and doubled full width to intercut the gores. Note that the front gores (A ) are joined straight to straight grain, and the back gores (B) are joined bias to straight grain, so that there will be no bias together on the side seams and they will not drop. The front of this farthingale has more at the bem than the back. The silk left over may be used for a hem. The farthingale is 1 1/2 baras long (49.5 inches) and the width round the hem slightly more than 13 handspans, which in my opinion is full enough for this farthingale, but if more fullness is required, it can be added to this pattern."

This used 6 Castilian Baras (5 1/2 yards) of silk fabric which was 22 inches wide. The large, squarish shape of the front (piece A) has the two gores marked A sewn to either side of it to create a flaring triangular front half. The two triangular gores are sewn to the front with their selvegde edges. The two triangular pieces marked B are sewn to the large B back piece by their bias-cut edges. Then the back half is sewn to the front, the straight selvedge edge of the B gore being sewn to the bias-cut edge on the A gore. As Alcega notes above, this results in no bias seams being sewn to eachother and eliminates the sagging which two bias seams sewn together would inevitably experience.

Once everything is sewn together, the farthingale would have been gathered at the top and the raw edges bound with a strip of fabric.As the triangular B gores are wider, and contain a few inches of fabric at the top, the back will have more fabric to be gathered than the front. There is no indication of where the opening is for this skirt (as is the case for all of Alcega's skirt & gown patterns), but given that there are references to farthingales being laced to corsets, it is reasonable to say that the opening would have been in the back or in the front for a front-lacing corset.

But was this spanish farthingale pattern the same used for English farthingales? The evidence is suggestive; 5 baras of 2/3-bara wide fabric was used in alcega's pattern. A bara is 33" inches long, giving us 25.2 square feet of fabric to work with. If you eliminate the extra 10 inches in length that Alcega's farthingale includes for women wearing chopines, the pattern uses 20.625 square feet of fabric.

The mid-16th century reference to "three ells of buckram" for a farthingale, if the flemish ell of 34" is used and the buckram is the expected yard in width, uses 20.25 square feet. It is very likely that a similar layout and pattern was used for making English farthingales.

Arnold's sketch of a farthingale made up based upon Alcega's pattern. from Patterns of Fashion 1560-1620

A farthingale made from Alcega's pattern. From Patterns of Fashion 1560-1620

Janet Arnold's analysis of Alcega's farthingale pattern explained the unusually long length--10 extra inches in length-- by taking up 10 inches of the length by sewing tucks in the farthingale for the hoops. This method has been adopted by many who want to reproduce a period farthingale. I disagree with this analysis, as all of the kirtles, skirts and gowns in Alcega's pattern book have the same unusual length to them; it was not peculiar to farthingales. A more likely explanation is that the skirts and farthingales were cut to accomodate the high chopine shoes worn by Spanish ladies. When worn without these shoes, the farthingale--and skirts worn over it--were tucked up near the hem, resulting in the front-tuck seen in several Spanish portraits of the late 16th century.

Farthingales--Get One of your Own!

There are several sites on the web with good instructions on making a Spanish Farthingale:

Patterns for making farthingales are available from The Tudor Tailor,Margo Anderson (with pictures and review of the pattern Here), Reconstructing History, Mantua Maker, and even Simplicity Patterns.

Or, if you aren't up to making a farthingale, you can buy them from several places on the web, including Historical Clothing Realm, Star Costumes or Designs by Rhenn.